With reproductive rights under attack, "reactionary feminism" is the last thing we need

Mary Wollestonecraft famously declared: “I do not wish [women] to have power over men; but over themselves.” It is hard to imagine anything more fundamental to a woman’s agency than the ability to control her own fertility, and modern technology can grant us just this kind of control. But, as last week’s Supreme court ruling in Alabama shows, legal rights to access to these technologies are far from settled.

Women in the US have always been on the front lines of the fight for reproductive freedom: in the early 1900s, when the first birth control clinics were being opened in Europe, the US was imprisoning people who sent birth control literature through the post. While a wave of Latin American countries have liberalised their abortion laws in the last 5 years, 14 US states have made abortion completely illegal following the overturning of Roe vs Wade in 2022. And reproductive control does not just mean family limitation: today, IVF has brought millions of much wanted children into the world. Last week, in Alabama, IVF services were suspended after courts ruled that frozen embryos were legal people (accidental embryo loss, or the destruction of unused embryos could now subject a clinic to murder charges). It is shocking to many of us in the post-enlightenment world to see written in a legal ruling that “even before birth, all human beings have the image of God, and their lives cannot be destroyed without effacing his glory."

But recent attacks on reproductive technologies are not just coming from the evangelical right. So-called feminists, spearheaded by self-styled “reactionary feminist” Mary Harrington, have been adding fuel to the fire. Their arguments that liberalised sexual norms and modern reproductive technologies are bad for women are hugely dishonest. Of course people who want to can abstain from using contraception, have sex only within a monogamous marriage, or rule out abortion as an option for themselves. But to universalise these values as a prescription for women’s best interests relies on willful misrepresentation of the facts. This should be obvious, but access to contraception is good for women. Access to safe and legal abortion is good for women. The sexual revolution has been, on net, good for women.

Take Harrington’s claim, in her book Feminism Against Progress, that the development of the contraceptive pill led to an increase in accidental pregnancy because of increased sexual activity. She doesn’t offer a reference, so it’s hard to know how she reached this conclusion, but it's totally wrong. Firstly, condoms, spermicidal pessaries, the withdrawal method, and the rhythm method were all in use well before the sixties. A large reduction in the numbers of children being born outside of marriage in late 19th/early 20th century Europe is attributed to increasing availability of contraceptives and education in this period. And in recent decades, rates of unintended pregnancy (that’s the number of unintended pregnancies per woman) have fallen everywhere in the world, and by almost 50% in Europe. While the causes of trends like this are obviously complex, studies show a clear link between use of contraception and a decline in unwanted pregnancy. Even if people are having more casual sex, this is resulting in fewer pregnancies.

Another conservative feminist voice is Louise Perry. She sensibly concedes that contraception has been good for female welfare, but in The Case Against The Sexual Revolution argues that permissive attitudes towards casual sex nevertheless harm women. Her argument that women face pressure to engage in “hook-up” culture is very similar to Harrington’s assertion that women suffer from “lack of a reason to say no”. In both instances, the implicit claim is that prior to the sexual revolution, women were having less unwanted sex. This seems unlikely. Somewhat ironically, a culture that prizes chastity makes it much harder to identify and sanction coercive sex, since there is social pressure for all women to present themselves as reluctant participants. Marital rape wasn’t even enshrined in law in the US or UK until the late 20th century. And sexual violence against poor women was particularly prevalent in the past. There are plenty of historic accounts of enslaved or servant women being “seduced” by their masters, where “seduction” should be read as “a sexual event that, in present times, could fall anywhere on the scale of sexual consent.” Rates of prostitution in the 1800s were staggeringly high: perhaps 1 in 10 women in London were selling sex. 1 in 10 children born at that time were abandoned. This was a “chaste”, pre-contraception society.

The fight for birth control is intimately related to issues of class. Harrington and Perry both try to paint liberal feminism as a bourgeois movement that fails to consider the needs of poorer and working class women, with Perry offering the truism that “it is the poor women who fare worst in the post-sexual revolution era.” Of course poor women fare worse than richer women today, as ever, but this difference was far more pronounced a hundred years ago. The truth is that, far from being elitist, technological and social sexual revolution has disproportionately benefited poor women, who have always had higher rates of fertility (due to less education and access to contraceptive methods), less protection from sexual violence, and less insulation from the consequences of unwanted pregnancy.

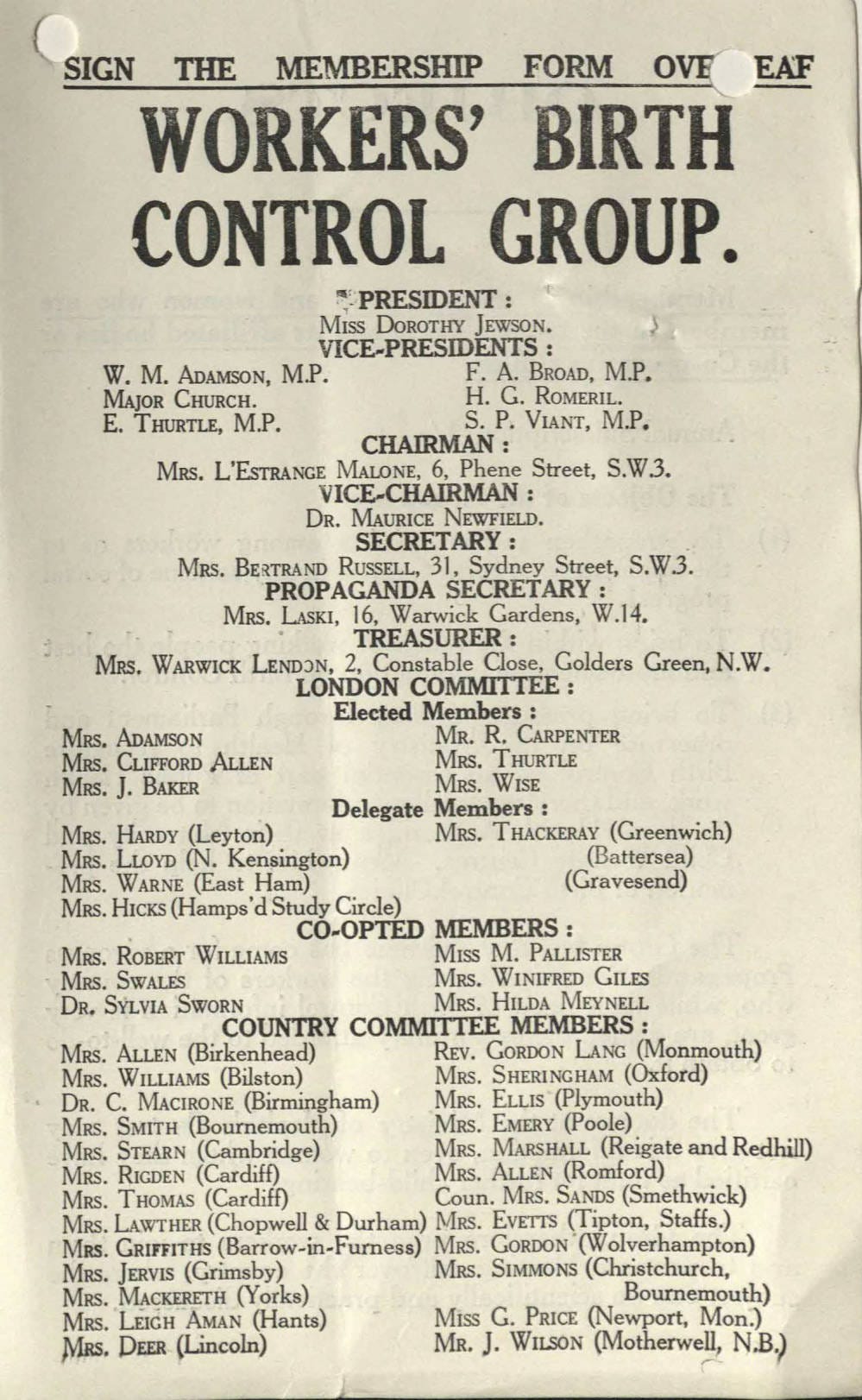

Margaret Sanger, who coined the term “birth control” and founded Planned Parenthood, saw her mission quite explicitly as the liberation of working class women. Sanger came from a working class background herself and was radicalised to her cause from the outset: she felt her mother’s death at 48 was partly attributable to her 18 pregnancies, resulting in 11 live births. Her criticisms of middle-class feminists in the suffrage movement were scathing: “let any Woman who labors for her bread enter any of these meetings and see what there is in the movement for her benefit, and she will be made to realize that there is no more for her in political freedom alone than there has been for her brother who has had his political rights for some time”. Sanger wanted attention paid to the material conditions of women’s lives, writing in her autobiography that “it seemed unbelievable that [feminists] could be serious in occupying themselves with what I regarded as trivialities when mothers within a stone’s throw of their meetings were dying shocking deaths.” Across the pond, when Marie Stopes pitched birth control as a technology for respectable middle-class wives Sanger criticised her for, among other things, being “anti-labor”.

Class isn’t the only progressive talking point co-opted by conservatives to attack sexual freedom. In 2015, a group of Republicans wrote an open letter to the Smithsonian demanding the removal of a bust of Margaret Sanger, on grounds that she was a racist who stood for the “extermination” of minorities. The first signatory was Ted Cruz, known for his opposition to same-sex marriage and abortion. In 2020, Planned Parenthood bowed to “relentless attacks” from the anti-choice right and removed Sanger’s name from their New York clinic. This was reported on by the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children, a conservative anti-abortion organisation, with the headline: “Planned Parenthood removes racist founder Margaret Sanger’s name from Manhattan clinic” (ironically, given how hated she is by opponents of abortion, one of the arguments Sanger frequently made for birth control was that it would reduce abortions). Soon after, the head of Planned Parenthood wrote a grovelling article for the New York Times, stopping short of actually calling Sanger racist (since, as they well know, she was not) but saying that they had behaved like an “organisational Karen”, whatever that might mean, and that a failure to denounce her “contributed to America harming Black women and other women of color”.

The truth is that to the extent to which the American Birth Control Federation (which later became Planned Parenthood) was criticised by civil rights activists at the time, it was for not doing enough to reach out to black communities. Segregation in the South meant that clinics opened there were not accessible to black women, which is why Sanger initiated the Federation’s Negro Project, managed by a board of eminent African American leaders and intellectuals, including W.E.B. Dubois and Mary McLeod Bethune.

Far from being hostile to minorities, Margaret Sanger was an active anti-racist who was praised by Martin Luther King. In 1966, Dr King accepted the Margaret Sanger award for human rights, saying: “There is a striking kinship between our movement and Margaret Sanger's early efforts. She, like we, saw the horrifying conditions of ghetto life. Like we, she knew that all of society is poisoned by cancerous slums. Like we, she was a direct actionist - a nonviolent resister. She was willing to accept scorn and abuse until the truth she saw was revealed to the millions.”

Dr King, like Margaret Sanger, recognised that birth control was a class issue and, by proxy, a race issue. In the same speech he says “Like all poor, Negro and white, [African Americans] have many unwanted children… There is scarcely anything more tragic in human life than a child who is not wanted. That which should be a blessing becomes a curse for parent and child. There is nothing inherent in the Negro mentality which creates this condition. Their poverty causes it.”

It is understandable that Planned Parenthood have distanced themselves from Sanger’s name; the dishonest, revisionist history that conservative activists have cynically spun has no merit, but it is a distraction from their mission and could deter minority women from seeking their services. But it is disappointing that they have legitimised the false association of birth control with racism, since it is black and other minority women who stand to benefit the most from access to family planning. African American women seek abortions at 5 times the rate of white American women, and mortality rates for black mothers are considerably higher than those for whites. In a comprehensive debunking of false narratives about Sanger and race, lawyer and women's rights activist Imani Gandy concludes that “Black women’s reproductive liberation has been weaponized by an anti-choice movement”. At least the outright moralism of Alabaman Justice Tom Baker is honest. Attempts to paint reproductive technologies as somehow ant-feminist, racist or classist are nothing more than cynical co-opting of progressive language to push a regressive agenda. Liberals must not fall for this nonsense.

Freedom from unwanted motherhood is absolutely fundamental to women’s emancipation. The other side of the coin is the ability to become a mother if one wishes. There are already significant financial barriers to accessing fertility treatment in the US, and for Alabamans this just became more pronounced. Those with means will of course travel to other states to seek IVF. Sanger says in her autobiography that she favoured the term “birth control” over “birth limitation”, because she had no wish to impose limits on fertility, just to put control into the hands of women. The fight for control over our sexual and reproductive lives continues, it remains an issue of racial and class justice and, of course, a feminist issue. Indeed, perhaps the most foundational feminist issue there is. As Sanger put it: “the basis of Feminism might be the right to be a mother regardless of church or state.”

Great piece, I didn't realize how much of the criticism of Sanger came from the right! When I had a set of pictures of folks throughout history I was a fan of in my office cube, the only one I ever took flak for was Sanger, on account of something to do with eugenics.

“Of course people who want to can abstain from using contraception, have sex only within a monogamous marriage, or rule out abortion as an option for themselves. But to universalise these values as a prescription for women’s best interests relies on willful misrepresentation of the facts. “

They’re expressing their opinion on the matter as you express yours. Reading your piece just gives off the impression that you’re frustrated that their argumentation of their position is carrying the day more and more versus the position you hold.

“This should be obvious, but access to contraception is good for women. Access to safe and legal abortion is good for women. The sexual revolution has been, on net, good for women.”

If it isn’t obvious (when it should be as you state), either the case hasn’t been made well or people just don’t agree with it. What’s obvious and good to me might not be so to you. That’s standard and it aligns with your previous comment about not universalising values across whole swaths of people.

And speaking of willful misrepresentation (as you characterised the reactionary feminist views) not once did you touch on that conservatives interest in curtailing, controlling or abolishing abortion is largely based on the fact that (in their view) it involves another person who’s interests are not being considered or protected (embryo). Writing a whole piece and only covering the interests of the woman to not have to give birth and neglecting the terminated fetus, is…well dishonest. Similar with Christians. Their purpose isn’t to control women but their concern is with the unborn. Seems like strawmanning at worst and incomplete discussion of the subject at best.

“Freedom from unwanted motherhood is absolutely fundamental to women’s emancipation.”

Yes, but it’s not like pregnancy is a condition that just appears and women need “freedom from it”. Women have agency and it’s patronising to suggest they need freedom in this instance.

Also don’t forget your earlier comment ….

“Of course people who want to can abstain from using contraception, have sex only within a monogamous marriage, or rule out abortion as an option for themselves.”

So are women who only have sex within marriage and rule out abortion not worthy of emancipation? Seems like a bizarre position.

I enjoyed reading your piece but I don’t think you pushed your view forward much given the points I highlighted above and more that I’m opting not to.