Women and Free Love: Part One

Free love, women's suffrage, and Mrs Satan

“If there is a more beautiful word in the English language than love, that word is freedom.” - Victoria Woodhull, 1871

What does it mean to love freely? And why is this a feminist concern? Today “free love” is mostly used as a euphemism for promiscuity, but the core idea of applying principles of liberty and autonomy to our sexual and romantic lives has been an important thread in Western cultural evolution over the last few centuries. Reforms to marriage and divorce, women’s civil and economic emancipation, gay rights, and the availability of reproductive technologies are all advances that owe to this tradition of thought. We are seeing some significant cultural pushback to sexual liberalism today, motivated partly by concerns about declining fertility, partly disquiet about the rise in transgenderism. There is a strand of conservative feminist thought that defends marriage and monogamy as institutions that protect women from male libidinousness, and sees women as harmed by permissive modern attitudes towards sex. This is what first got me interested in historical biographies of women who saw free love as a feminist issue and went to great lengths to live by and promote its ideals. What kept me interested is that, as Oscar Wilde wrote, history is merely gossip1, and these stories contain some great gossip.

I couldn’t possibly condense all my favourite free loving women into a single article, so this will be part one of several.

Part One: Women’s suffrage and Mrs Satan

The phrase “free love” was probably first coined in 1846 by a preacher called John Humphrey Noyes, and his conception of it was pretty radical even by today’s norms. Noyes and his wife moved in with another couple and lived as a foursome in what they referred to both as a “complex marriage” and a system of “free love”. They went on to found the Oneida Community, a utopian experiment combining communist and Darwinist ideas, where property was communal and so was sex. At Oneida, sex was to be freely enjoyed but pregnancies carefully planned, with parents chosen for their apparent genetic compatibility rather than any romantic ties. Noyes called this approach to reproduction “stirpiculture” - a clunky term that predated Francis Galton’s “eugenics”2. Advocacy of free love and advocacy of eugenics often coincided over the next century, although the link between the two varied in flavour. Some, like the Oneidans and later, the birth-control advocates, made eugenic arguments for the decoupling of sex and reproduction. On the other hand, some believed that freely following sexual instincts would produce the best offspring; for example, the well-known anarchist Stephen Pearl Andrews suggested in 1886 that “woman, when free, should exhibit an inherent God-given tendency to accept only the noblest and most highly endowed of the opposite sex to be the recipients of her choicest favors, and the sires of her offspring”3.

As the free love label was adopted more widely, it didn’t remain synonymous with what we today might call polyamory. Its popular meaning was much more broad and literal - that everyone should be free, both socially and legally, to love as they choose. Free lovers argued both for the minimisation of the state’s role in romantic unions, and for broad social acceptance of a variety of romantic and sexual predilections (among heterosexuals: in the mid to late 1800s the discourse was more or less exclusively about relations between men and women and it took several more decades before the obvious extension of this principle to same-sex attractions was defended). Within the free love movement there were significant disagreements: some wanted to abolish marriage entirely, others simply to reform divorce. Some only argued for freedom to enter and exit exclusive relationships and criticised promiscuity, others argued that non-monogamy was permissible or even optimal.

A summary of the latter dispute can be found in the 1857 book “Free Love: Or, a Philosophical Demonstration of the Non-exclusive Nature of Connubial Love” by Austin Kent:

“We all teach that the laws of mind are our guide; and that these laws must be absolutely Free. In this sense, we all contend alike for Free Love. We agree that healthy affinities and attractions must reign supreme. But Mr. Wright, and some others, tell us that this healthy attraction will, and must, in its nature, be always exclusive. I hear some, on the other hand, say to Mr. Wright and his friends,— "Hands and opinions off! Allow us the freedom to settle the nature of our own attractions. Admitting you may know what is most healthy, elevating, and pure for yourself—do not measure all men and all women by your own affectional stature!"

Kent himself argued that truly exclusive romantic love was unheard of: “none, in entire freedom, and uninfluenced in the past and present by other minds or institutions in the bondage of the past or present,—would ever be absolutely exclusive in any of the manifestations of connubial love.” But he also defended the diversity of human tastes, saying that “different minds differ as to their leanings towards entire exclusiveness, or its opposite—absolute promiscuity.”4

Criticism of the institution of marriage from a feminist perspective had been around for much longer. In her 1792 pamphlet, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, British philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft characterised marriage as “legal prostitution”. She went on to write a didactic novel called, riffing on the title of her previous work, The Wrongs of Woman, featuring parallel stories about a working class woman cast out of her master’s house after becoming pregnant through rape and an upper class woman who flees her abusive marriage after also becoming pregnant through marital rape. She advocated for women to be educated and have opportunities to live by their own means, to have “power… over themselves”. Praising chastity as a virtue and criticising “libertines”, Wollstonecraft’s attitude to sex was prudish by modern standards, but at the time she lived she was a sex radical, pilloried for having a child out of wedlock and entering into two “free unions” - non-marital sexual relationships. Almost a century later, suffragist and US presidential candidate Victoria Woodhull echoed Wollstonecraft’s ideas in her 1873 speech The Scarecrows of Sexual Slavery, comparing marriage to prostitution and condemning marital rape. Woodhull, not shy of controversy, put it with characteristic flair: “They say I have come to break up the family; I say amen to that with all my heart. I hope I may break up every family in the world that exists by virtue of sexual slavery.”5

In the late 1800s, Victoria Woodhull’s name was synonymous with the free love cause. She was influenced both by feminists, and by anarchists and sex radicals including Stephen Pearl Andrews, who had become her intellectual mentor. Woodhull is an absolutely fascinating character: born poor, she came up through the American spiritualist movement, which allowed women to command large audiences as celebrity mediums. After making names for themselves as clairvoyants, she and her sister Tennessee Claflin founded the first female-run stock brokerage on Wall Street and used the money they made to start a radical newspaper, Woodhull & Claflin Weekly. Edited by Woodhull’s second husband Colonel James Blood, the Weekly published a range of radical thinkers: Marxists, suffragists, anarchists, and plenty of free lovers.

Both sisters were determined to defy the limits placed on women and delighted in scandalising people. For several years at the height of their notoriety, Woodhull and Claflin were the most frequently depicted characters in New York’s illustrated tabloids6. They cut their hair short and dressed like men, lived communally in a house their mother called “the worst gang of free lovers… that ever lived”7, and hosted salons that Pearl Andrews compared to those of French revolutionary Madame Roland. Between the two of them they racked up a number of firsts for women: first female stock-brokers, first woman to address the House Judiciary Committee (Woodhull, on the subject of women’s suffrage), first female Colonel (Claflin, 85th regiment of the New York national guard), first woman to run for president (Woodhull, as nominee of the newly founded Equal Rights Party). They were women of action. As Victoria put it in a letter to the New York Herald announcing her presidential candidacy: “while others prayed for the good time coming, I worked for it; while others argued the equality of woman with man, I proved it by successfully engaging in business.”8

Woodhull was an incredible orator and drew large crowds to her speeches, probably ghost-written by Pearl Andrews. These included impassioned criticisms of the “sexual slavery” of marriage, defences of non-monogamy, and eugenic arguments for women’s reproductive freedom. The latter was a personal issue for her after having a cognitively disabled child by her abusive first husband at the age of 15. She attributed her son’s disability to his father’s alcoholism, and this motivated her activism: “Do you think my mother’s heart does not yearn for the love of my boy?… Do you think I would not willingly give my life fto make him what he has a right to be?… Do you think I can ever hesitate to warn the young maidens against my fate, or to advise them never to surrender the control of their maternal functions to any man!”9.

While openly praising the Oneida community and defending the right to promiscuity, Woodhull was somewhat evasive about her own love-life. But, as she argued, her own preferences were not the point: she was defending “sexual freedom for all people - freedom for the monogamist to practice monogamy, for the varietist to be a varietist still, for the promiscuous to remain promiscuous.”10 On her support for individual sovereignty, she was never evasive: “Yes, I am a Free Lover. I have an inalienable, constitutional and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere.”11

The most direct evidence of Woodhull practising what she preached is the account of Benjamin Tucker, a young anarchist who worked with Victoria during her years in New York and described losing his virginity to her at the age of 19. He describes himself as “bashful, shy, timid” and with “sexual instincts not yet awakened”, although he sympathised intellectually with “the struggle for sexual freedom”. He was introduced to Woodhull by her second husband and close collaborator Colonel James Blood, and she soon made a move on him, saying “do you know, I should dearly love to sleep with you?” Tucker paints a picture of casual, open polyamory. After Victoria seduced him, Tucker reports that he asked her “what will Col. Blood think of this?’. “‘Oh, that will be all right,’ she replied, ‘and, besides, he cannot deny that it’s largely his own fault. Why, only the other day he wrote to me of you in glowing terms, declaring, “I know very well what I would do, were he a girl.”12

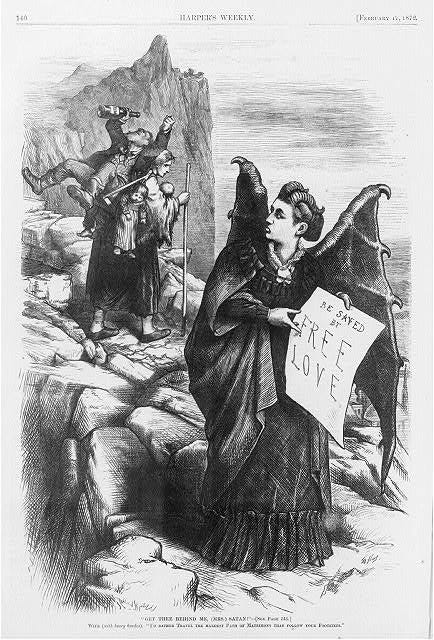

Woodhull’s determined advocacy of free love made her something of a political liability for her suffragist peers. In 1972 Harper’s Weekly published an article calling her ideas “Satanic”, with an accompanying illustration by the famous political cartoonist Thomas Nast depicting Woodhull as “Mrs Satan”13. Although the article is condemnatory, Nast’s cartoon retains a certain ambiguity: in it, a woman carrying a drunk husband and screaming children on her back rejects the devil Woodhull and her message. But if some were sympathetic to her cause, on the whole it was not a popular one. Associating women’s civil rights with free love risked delegitimising the former, but Woodhull was adamant that “suffrage is only one phase of the larger question of women’s emancipation”14. Meanwhile, suffragist leader Susan B. Anthony allegedly wrote in private that Woodhull was “the first woman man had succeeded in fashioning to his own ideal - so that she theoretically accepted man’s practical theory of promiscuity”15. And when Anthony and others published the three volume book History of Women Suffrage, Woodhull’s contributions were mostly relegated to footnotes.

In 1872, the year Woodhull ran for president, Woodhull, Claflin and Bood were set up by self-appointed enemy of vice Antony Comstock. Woodhull & Claflin Weekly had published a lurid expose of the extra-marital affair of a famous preacher (possibly after a failed attempt to blackmail said preacher into endorsing Woodhull for president). Comstock ordered a copy of the paper, and then had the three arrested and charged under an 1865 law against sending obscene material through the post. Even Woodhull’s detractors were outraged by this, and many articles were written in support of the defendants’ rights to free speech. In the year of her candidacy Woodhull spent the presidential election in jail, but after finally being acquitted on a technicality (that newspapers were exempt from this law), her profile was higher than ever. Although her presidential campaign was over, she cashed in on her fame, lecturing to large audiences around the country. Comstock, meanwhile, went on to tighten federal anti-obscenity laws with the Comstock Act of 1873, which would be used extensively in the coming decades to obstruct the work of birth control campaigners.

It is hard to get the measure of Victoria Woodhull as a person. She was at various times a stockbroker, a communist, a clairvoyant, a presidential candidate, a blackmailer, a free-speech martyr, the most famous suffragist in America, and written out of feminist history by her contemporaries. And, after a decade making her name synonymous with free love, in 1876 she completely reinvented herself. She ended her 10 year marriage to Blood for reasons that aren’t clear, and moved to England with her two children and sister Tennessee. Woodhull then embarked on an aggressive image laundering process, distancing herself from the free love movement and limiting the focus of her lectures to eugenics and more respectable aspects of women’s rights. Although she was still advocating for women’s sexual freedom, now predominantly under the auspices of eugenic feminism, she denounced the free love label, a term she once said she was willing to “live or die by”16. After successfully rehabilitating her public image she married a wealthy banker and spent her last decades enjoying life among the British elite. And it wasn’t just Victoria who completed an incredible rags to riches journey by marrying into a wealthy upper-class British family. Tennessee, born dirt poor in rural Ohio, spent the second half of her life as Lady Francis Cook, Viscountess of Montserrat.

If there’s one thing that can be said for both Tennessee Claflin and Victoria Woodhull it’s that they demonstrated incredible self-belief, coupled with a life-long refusal to be constrained by either gender or conditions of birth. Never one to undersell herself, Woodhull’s own assessment of her political career is a perfect demonstration of her character:

“To be perfectly frank, I hardly expected to be elected. The truth is I am too many years ahead of this age, and the exalted views and objects of humanitarianism can scarcely be grasped as yet by the unenlightened mind of the average man”. - Victoria Woodhull, 1892.17

Wilde, Oscar (1893). Lady Windermere's Fan (1st ed.). London: The Bodley Head. Wilde.

Wayland-Smith, E. (2016). Oneida: From free love utopia to the well-set table. Picador.

James, H. Sr., Greeley, H., & Andrews, S. P. (1889). Love, marriage, and divorce, and the sovereignty of the individual: A discussion.

Kent, A. (1857). Free Love Or A Philosophical Demonstration Of The Non-Exclusive Nature Of Connubial Love. Hopkinton, N.Y

Woodhull, V. C. (1874, May 30). The scare-crows of sexual slavery. Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly.

Frisken, A. (2004). Victoria Woodhull’s sexual revolution: Political theater and the popular press in nineteenth-century America. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Underhill, L. B. (1995). The woman who ran for president: The many lives of Victoria Woodhull. Bridge Works.

Woodhull, V. C. (1870, Apr 2nd), Letter to the New York Herald.

Woodhull, V. C. (1873). Tried as by fire: Or, the true and the false, socially. An oration delivered by Victoria C. Woodhull in all the principal cities and towns of the country during an engagement of one hundred and fifty consecutive nights. Woodhull & Claflin.

ibid.

Victoria C. Woodhull (1871). "And the Truth Shall Make You Free." A Speech on the Principles of Social Freedom, Delivered in Steinway Hall, Nov. 20, 1871, by Victoria C. Woodhull (Woodhull, Claflin & Co., Publishers, 1871)

Sachs, E. (1928). The terrible siren: Victoria Woodhull (1838–1927). Harper & Brothers.

“Mrs Satan” (1872, Feb 17). Harper’s Wreekly.

Woodhull, V. C. (1896). Women’s suffrage in the United States. The Humanitarian: A Monthly Review of Sociological Science. New York and London.

Sachs, E. (1928). The terrible siren: Victoria Woodhull (1838–1927). Harper & Brothers.

Letter to Elizabeth Bladen (1871, Jun 22). Garrison Family Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Underhill, L. B. (1995). The woman who ran for president: The many lives of Victoria Woodhull. Bridge Works.

Thank you for the history lesson. I did not realize she was from America. I read a lot of historical romance novels and the authors talked about her a lot. I’m ready for part 2!!!